Transforming healthcare through a trauma-informed patient experience

Care delivery models and patient experience initiatives must be primarily informed by learning and hearing directly from patients.

Hearing the words, “Your child has cancer” is traumatizing.

If you even register the words in your mind at all, the words conjure up graphic and morbid images of a parent's worst nightmare.

Usually, the journey for those words to reach you isn’t straightforward either.

For my son, we spent four days leading up to a cross-country move trying to problem-solve why my 5-month-old son wasn’t keeping his food down and seemed more tired than usual. We were watching his fontanel – the soft spot on the top of his head – for signs of dehydration, but everything appeared as we would expect. So, after cluster feeding to stay hydrated, calling the pediatrician for assurance, and more waiting and watching, I decided to bring him into the local children’s hospital to get fluids to help fight off whatever he was fighting.

When we arrived at the hospital, the lighting of the waiting area triggered my mother’s intuition alarm. Something wasn’t right as I held my son in the fluorescent shadows. My 99th percentile in both height and weight exclusively breastfed baby boy looked remarkably faded. Thankfully, the triage nurse validated my intuition, and we were swiftly moved into the ICU bay of the emergency department.

From concern to emergency care

The ER doctor who was working the Friday night shift seemed equally curious about what we were dealing with and suggested a CT scan of his head because “the soft spot on his head felt a bit firmer than expected in a child his age.” As quickly as we were brought into a room, my sweet boy went off to get a CT with a crew of clinical staff while I waited behind in the empty bay for him to return.

As I was sitting in a plastic chair outside of the room waiting for the results, I spotted the ER doctor walking towards me with urgency. She knelt in front of my chair with a sigh and her hands folded as if praying.

“Fuck,” she said. And took another breath.

“We found a large mass at the base of his skull, which is causing something called hydrocephalous,” she continued. “He needs to get in front of the neurology team downtown as soon as possible, and I’ve already called a Care Flight that is on its way to transport him there.”

Blinking several times over, my ears started ringing and my vision seemed to narrow. My beautiful, healthy boy has a mass? How could that be? What does that mean? How does that happen? My mind was spiraling.

“Mama, how much do you weigh? You can go with him on the flight.”

I zapped back into reality.

“And while we wait, try to keep him alert however you can. Sing or talk, but we want you to stay with him and keep him awake.”

I moved to his bedside, stroked and kissed his forehead.

“Sweet boy, I love you so much.”

And I started to sing a song I made up after he was born that I would sing to him often.

“Little baby August, sitting in a tree,

S-M-I-L-I-N-G.

Little baby August, looking up at me,

S-M-I-L-I-N-G.”

Within minutes, the Care Flight arrived, and we were flown downtown to meet the neuro team for more answers. Funny enough, beyond the immediate emergency at hand, my brain was also processing the fact that it was my first time in a helicopter – and I couldn’t stop thinking about how my older son would have been so excited to know that we got to fly in one. And somehow, I managed to get a picture for him.

The weekend became a flurry of diagnostic procedures to learn more about what we were dealing with. Tumors like this aren’t a common thing in infants, so there were more questions than answers for a while. The weekend was punctuated with a 14-hour surgery on the following Monday to attempt to resect (the clinical term for remove) the tumor that had wrapped around my son’s brainstem and spinal cord and pancaked his cerebellum. He was not supposed to survive. But he did.

Becoming an advocate

For two weeks, we waited for the pathology report to let us know what kind of brain tumor had infiltrated my little boy. For two weeks, we spent those dreary and loud days in the trauma-ICU and later neurology floors focused on recovery. For a 5-month-old, that primarily looked like regaining head control – a milestone he had just achieved a few months earlier - and attempting to resume breastfeeding. Unfortunately, there was not a shared consensus among the providers and clinicians on the value of breastfeeding because August was an aspiration risk.

Despite that resistance, armed with my own research, a blessing from the inpatient speech therapist, and persistent and confident advocacy, I found myself stretching my wings as a caregiver and patient advocate for the first time, determined to give my son the best chance at a full recovery – even if no one else believed it was possible.

Remarkably, the advocacy was effective, and I was permitted, with feeding therapy support, to resume breastfeeding directly. After two weeks of struggle, my son and I were able to come back to an innate comfort we both knew, and we both could truly begin to heal.

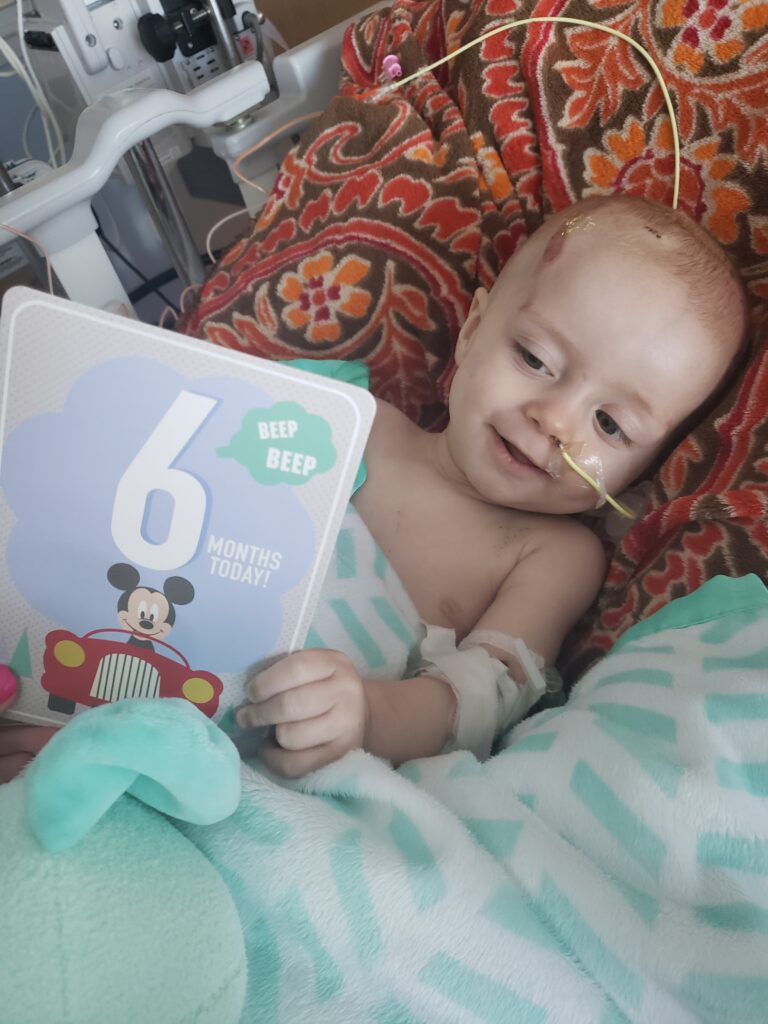

Then, on the afternoon of August’s 6-month-old “birthday,” the neurosurgeon who masterfully saved my son two weeks earlier came into our room to tell us those fateful words: “Your child has cancer.”

My ears started ringing again, my vision narrowed, and my heart rate jumped. I wanted answers, but knowing this information did not comfort me.

Patient experience at its core

This story is a patient experience.

This story was the start of my son’s patient journey and the start to my experience more formally as a caregiver and advocate. This story sits among hundreds of others that we experienced in the past five years. Although this “superhero origin story of sorts” doesn’t define our experience, it has shaped our perspective of healthcare in the United States, and it has helped us see the opportunities available to make the system better for others.

To create a healthcare delivery model centered around the patient experience, we must consider stories like this. We must recall the details of the diagnosis experience, including its milestones. We must recognize the relationships involved in the patient’s care and how they connect to the outcomes we all aim to achieve.

Additionally, we must consider the context of the healthcare experience, the trauma endured, and how the family is equipped to support the patient in the healing process.

Our personal story is unique, but similar stories happen daily across the country. Every patient story carries its own nuances, influences, context, and timing. Like fingerprints, no two are alike; importantly, you can’t “make it up.” Care delivery models and patient experience initiatives must be primarily informed by learning and hearing directly from patients. You cannot hypothesize a patient’s experience in your hospital or practice.

Designing workflows and care models that consider the subtleties of the patient’s experience is exceptionally challenging. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement has made a beautiful attempt at a guiding principle for healthcare industry transformation with The Quintuple Aim, accommodating post-COVID requirements like clinical burnout and equitable access to care. However, despite these best intentions, an all-encompassing factor influencing the outcomes-inspired model has yet to be fully considered: trauma.

When traumatized, our brains work differently, especially during acute, life-or-death situations, putting our bodies and minds into uncharted territory. Trauma impairs executive functioning skills like critical thinking, problem-solving, comprehension and task management. How many patient experience initiatives seek to engage patients in this way?

Over the years, patient experience initiatives I’ve witnessed seem to engage patients and their caregivers to bridge administrative gaps in care that the system or facility fails to address, not to improve health outcomes. As a cynic, this is an abomination. As an optimist, therein lies the opportunity.

A trauma-informed approach

What if we reimagined the Quintuple Aim in a trauma-informed way? What if cost-of-care initiatives recognized that more than three out of five bankruptcies in the United States result from medical debt and that more than half of Americans are extremely concerned that a major health event could lead to bankruptcy?

Could a trauma-informed Quintuple Aim realign care delivery models with outcomes-based reimbursement? Could we celebrate the experiences of patients and caregivers differently?

Instead of placing an administrative burden onto the patient or caregiver and calling it “patient experience,” a trauma-informed approach could be as simple as celebrating the patient and caregiver eating a meal, taking a shower, listening to a song or going outside to feel the sun on their face. Ask any cancer survivor, rare disease patient, or caregiver about their most impactful healing tools, and these flavors of self-care will surely be mentioned.

A trauma-informed approach could also address another urgent need: clinical burnout. Clinical burnout results from exhaustion, desperation, and extraordinary odds but is more succinctly the result of unsupported and unhealed trauma. What if there was a trauma-informed way to support the clinical experience of care?

Healthcare is at an inflection point, a reality echoed in countless articles across LinkedIn. However true, healthcare will continue no matter what we do. Healthcare delivery is anchored in our human experience, as long as we have bodies and minds that are born and die, healthcare will be delivered in some form.

If we want to believe that a healthcare model can remedy some of our most taxing and costly human experiences – like a cancer diagnosis, a life-changing accident, a chronic disease, a rare disease, or aging, we would be wise to adopt a trauma-informed approach throughout our initiatives. A trauma-informed healthcare model isn’t just a compassionate choice. A trauma-informed model of care is supportive of human experience and can lead to healing – and thriving.

Erica Olenski is associate vice president of FINN Partners.